The California Grizzly Bear, Long Gone but Still Here

By Sasha Coles

Noble and vicious. Awe-inspiring and monstrous. Beautiful and dangerous. For hundreds of years, people used this mixture of adjectives to describe the California grizzly bear, a subspecies of the North American brown bear that populated the chaparrals, valleys, and mountains of the Golden State. What we know about this grizzly bear comes to us from the explorers, trappers and traders, scientists, and laypeople who encountered and shared stories about this animal. Today, the grizzly endures as a symbol of California. You can find the animal on the state flag, in the names of streets and natural landmarks, and in the stone edifice on top of Grizzly River Run at California Adventure. While you can see this critter all over the place, you cannot actually find one. Scholars figure that it only took sixty years for Californians to push this “lord of the forest” over the threshold to extinction. Now, scholars must rely on diaries, newspaper articles, letters, and reports to trace the story of this creature and tease out fact from fiction, myth from reality.

The history of the California grizzly bear predates “California” by thousands of years. Beginning in the Pleistocene Epoch, the place we know as California offered a paradise for the bears. As many as 100,000 of them ventured over the land, finding their fill of fish and other seafood, acorns and grasses, berries and clover, honey, and roots. They lived alongside an estimated 350,000 indigenous peoples, belonging to 500 distinct sub-groups, before the Spanish arrived in the 1700s. Bears carried deep significance for their human neighbors, who hunted the animals and incorporated them into complex traditions. For example, Modoc and Shasta Indians articulated an origin story for the bear that also explained the beginnings of humanity. Before people lived on Earth, the Great Spirit made the Grizzly Bear out of his walking stick. All grizzlies walked on two feet back then. One day, the Wind Spirit swept the Great Spirit’s daughter away. Grizzly Bear found the daughter and brought her home to his family. Mother Grizzly raised the girl alongside her cubs. When she got older, the Great Spirit’s daughter married Grizzly Bear’s eldest son, and the pair’s children were the first Indians. As Mother Grizzly neared the end of her life, she sent her eldest grandson to tell the Great Spirit that her daughter was alive. The Great Spirit responded with fury and cursed all grizzlies to walk on four feet for the rest of eternity.

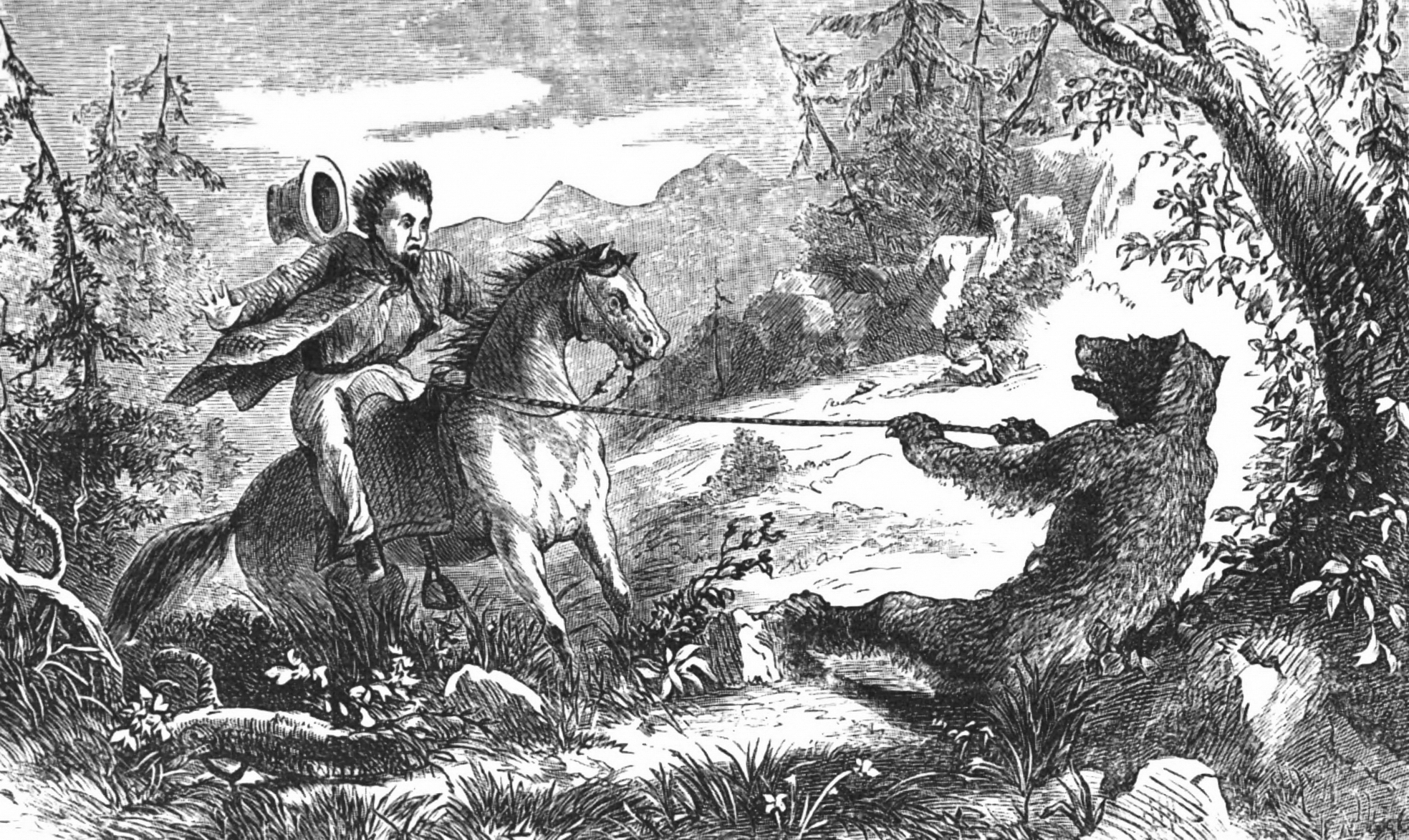

One man told a story about a grizzly bear with enough strength to drag him and his horse. Ernest Narjot, “The Pull on the Wrong Side” from A la California: Sketches of Life in the Golden State by Albert S. Evans (San Francisco: A. L. Bancroft, 1873).

Europeans “discovered” the grizzly bear when they came to the coast and colonized the area. Over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, humans came to know the bears as valuable commodities, insatiable predators, and a form of entertainment. The first known recorded description of the California grizzly bear comes to us from Antonio de la Ascensión, a Spanish priest who mapped the California coast as part of the Vizcaino Expedition. In December 1602 he described these bears as “so large that their feet are a good third of a yard long and a hand wide.” In 1790 Edward Umfreville, a Hudson Bay Company writer, used the word “grizzle” to describe a California bear with silver-tipped fur. Five years later a Scottish explorer named Alexander MacKenzie called the bears “grisly” because of their fear-inspiring characteristics.

The colonists who put down roots in early California did not much appreciate these creatures. In order to encourage settlement in California, the Spanish government offered land grants known as ranchos. Rancheros, or the people who raised cattle, sheep, and horses on ranchos, frequently complained about grizzlies attacking their livestock. Spanish padres hired men to rid the land of the predators. Many obliged. At this point, a grizzly hunter could earn a good living selling bear products, including pelts, meat, and oil for cooking and hair grease. The Spanish were also fond of bear fights, which became a critical part of weekend leisure and community celebrations. People pitted bears against donkeys, cougars, cows, and Spanish bulls (with sawed-off bull horns to ensure a “fair” fight). Organizers goaded the animals with knives and starved them to make them angry and desperate.

"Grizzly" Adams posing with his menagerie. Edward Vischer, “Adams, the Hunter, and His Bears” from Vischer’s Pictorial of California (San Francisco: Printed by J. Winterburn & Co., 1870).

Despite the pressures of human intervention, the California grizzly bear survived well into the nineteenth century. These creatures attracted quite a bit of fame and a fearsome reputation, based mostly on stories—some true, many exaggerated—about violent encounters. Some (smart) people saw the bears as an inconvenience and kept their distance. Others unintentionally bothered the bears and paid a hefty price. In 1823 a grizzly bear mangled Hugh Glass, a famous fur trapper and explorer, while he and his company hunted for food in the South Dakota region. His comrades took Glass’s rifle and belongings and left him for dead, but Glass overcame his injuries and successfully completed the one-hundred-mile trip to Fort Kiowa. Experiences like these encouraged mountain men in California to pursue and kill native grizzlies in order to prove their masculine prowess. They wore grizzly claws as trophies and brought back tall tales about monstrous twelve-foot-tall bears weighing in at three thousand pounds. One man told his comrades about a bear who continued to fight after suffering sixty bullet wounds. George Yount, a trapper living in 1850s San Francisco, bragged to writer F. H. Day that he often killed five to six bears per day. While these hunters frequently exaggerated the details of their encounters, their personal writings and descriptions provide today’s scholars with the most helpful information about the bears. These men familiarized themselves with the habits and habitats of the bears and described them in intimate detail.

Rutledge & Gillespie, “Performing Bears in Woodward’s Garden, San Francisco”

Grizzly bear numbers peaked in the mid-nineteenth century, and public fascination with the animals grew. People began stealing cubs from their mothers and training them to play instruments, dance, and wrestle. James Capen Adams, a mountain man and commercial hunter, earned the nickname “Grizzly Adams” for his skill in capturing and training bears for show business. Adams traveled around with his fully-grown bears, which he named Lady Washington, Fremont, Ben Franklin, and Samson. They walked in parades and performed at opera houses and theaters. In the 1850s he put a number of animals—elk, lions, tigers, deer, and bears, among others—on display in a San Francisco basement. He and his pets traveled to the east coast in the summer of 1860 to collaborate on a show with P. T. Barnum. A gruesome bear attack (surprise, surprise) that Adams suffered in 1855 bothered him more and more, however, and forced him to end the show. The public could still find live grizzlies in other places. As many as 20,000 people turned out to see Monarch, a bear captured in Ventura County in 1889, when Woodward’s Garden in San Francisco opened. Monarch lived there for twenty-two years and weighed in at 1127 pounds when his keepers euthanized him.

An advertisement for the Lemon Grower’s Association, San Bernardino, CA.

It turns out that Americans preferred seeing grizzly bears from a safe distance, or as zoo animals and taxidermized statues, in other words. As white people converted the land to orchards and fields, they increasingly viewed bears as “vermin” that threatened the image of California as a sophisticated, safe, and bountiful place. Farmers sowed their property with strychnine to protect their sheep and cattle herds. People who killed grizzlies garnered reputations as heroes and protectors of women, children, and family pets. A small minority of folks, including Joseph Grinnell of the University of California’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, tried to stymie the grizzly extermination, or at least preserve a complete sample for scientific research, but these arguments fell on deaf ears. High mortality rates combined with a loss of habitat wreaked havoc on the grizzly population. The last reported sighting of a wild California grizzly bear occurred in 1925, but these bears still live on as myths and symbols. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century advertising used grizzlies to sell California produce. The University of California used the bear as a mascot in the 1890s, and the California grizzly became the state’s official animal in 1953. It is true that the California grizzly bear is long gone, but you can help preserve the animal’s history the next time you visit California Adventure and take a harrowing white-water rafting adventure through the Sierra Nevadas. Don’t forget your rain poncho!

If you liked reading this Disney-inspired history article, be sure to SUBSCRIBE to get updates on new posts and other exciting Enchanted Archives news!

Sources

Susan Snyder, Bear in Mind: The California Grizzly (2003)

Peter Alagona, After the Grizzly: Endangered Species and the Politics of Place in California (2013)

An Account of Hugh Glass’s Bear Attack

You can visit the grizzly’s ancestors at the La Brea tar pits in Los Angeles.