The Jungle Cruise: Romance, Adventure, and the Legacies of Colonialism

By Ryan Minor

Let’s play a game, shall we?

I’m going to mention a word, and I want you and everyone you’re with to remember the first thing you think of when you hear it. Are you ready? Here’s the word: AFRICA.

What did all of you think of? No cheating now, only the first thing that popped into your head counts. Chances are that you thought of something wild or primitive. A lion or a zebra? People wearing masks and throwing spears? A desert? Conflict, famine, or slavery? Perhaps you imagined a Jungle Cruise skipper escorting you down the Congo and the Nile. I can practically hear the corny jokes they tell as they steer you clear of hippos, piranhas, and a savvy headhunter named Trader Sam.

The Banks of the Upper Congo. H.M. Stanley, The Congo and the Founding of its Free State; A Story of Work And Exploration (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1885).

Here are some other facts about Africa that often go overlooked. Africa is the second largest continent on the globe. It has fifty-four different countries, a total population of 1.2 billion people, thousands of distinct cultures, and some of the world’s largest cities (Lagos in Nigeria has a population of 21 million). It is also home to some of the world’s longest continuous civilizations, including Egypt, Ethiopia, and the Swahili Coast, and one of the oldest universities, Sankore in Timbuktu. This institution has been an important site of Islamic knowledge production since the twelfth century.

So why is it that, regardless of Africa’s true diversity and history, most of us tend to associate the continent with mysterious jungles, dangerous spear-throwers, or exotic wildlife? When Walt Disney described Adventureland, he said, “Here is Adventure. Here is Romance. Here is Mystery. Tropical rivers—silently flowing into the unknown. The unbelievable splendor of exotic flowers…the eerie sounds of the Jungle…with eyes that are always watching.” Where do these notions about Africa come from, and why should we care? To begin to answer these questions, we must first return to nineteenth-century Europe.

A Scramble for Africa

Map of Colonial Africa in the early twentieth century. Credit: Whiplashoo21.

In 1884, representatives from fourteen European countries met in Berlin to discuss their interest in developing colonies in Africa. The years following this Berlin Conference witnessed a period of rapid colonization known as the “Scramble for Africa.” By 1914, European nations controlled nearly the entire continent. When Disneyland opened in 1955, all of sub-Saharan Africa was still subject to European colonialism. In order to justify their presence, these nations promoted ideas of Africa as a primitive and “dark” place, in need of the “light” of Western enlightenment and progress.

One of the attendees of the Berlin Conference, King Leopold II of Belgium, acquired a portion of central Africa roughly 905,000 square miles in size (that’s about 80 times the size of Belgium itself). He named the colony the Congo Free State and set it up as a private, non-governmental organization promising to bring progress and Christianity to the region. Leopold, the sole shareholder of this NGO, enjoyed complete control over the territory. Contrary to its name, the Congo Free State would play host to one of the worst cases of African oppression in the history of colonialism. From 1885 through 1908, Africans worked as slave laborers, harvesting rubber sap and collecting ivory. The extraction of these resources made Leopold one of the wealthiest individuals in Europe, while an estimated three to ten million Africans perished from overwork and disease.

Joseph Conrad and Heart of Darkness

In 1890, author Joseph Conrad spent six months working for a Belgian shipping company on a steamship heading up the Congo River. Later in life, he described what he witnessed as “the vilest scramble for loot that ever disfigured the history of human conscience.” Conrad published a story loosely based on his experiences from that time. He called it Heart of Darkness (1899).

Conrad’s combination of vivid storytelling, flare for adventure, and progressive critique of the worst forms of colonialism catapulted Heart of Darkness to instant fame. To this day, many critics consider it one of the great works of English literature. I bet some of you even read Heart of Darkness in school. Throughout the story, Conrad focused on the process of Europeans becoming uncivilized once exposed to the wilds of Africa. This transformation suggested that the environment, rather than innate, biological difference, separated “the races” from each other. While the idea of a shared humanity among all people was fairly forward-thinking for the time, unfortunately, Conrad’s description of Africa does very little to challenge nineteenth-century notions of the continent as a primitive symbol of Europe’s past. Take these two passages, for example, which have a lot in common of what Jungle Cruise passengers see during their journeys:

“Going up that river [the Congo] was like travelling back to the earliest beginnings of the world…On silvery sandbanks hippos and alligators sunned themselves side by side…you lost your way…till you thought yourself bewitched and cut off forever from everything you had known once—somewhere—far away in another existence perhaps.”

“It [Africa] was unearthly, and the men were—No, they were not inhuman. Well, you know, that was the worst of it—this suspicion of their not being inhuman…They howled, and leaped, and spun, and made horrid faces; but what thrilled you was just the thought of their humanity…the thought of your remote kinship with this wild and passionate uproar.”

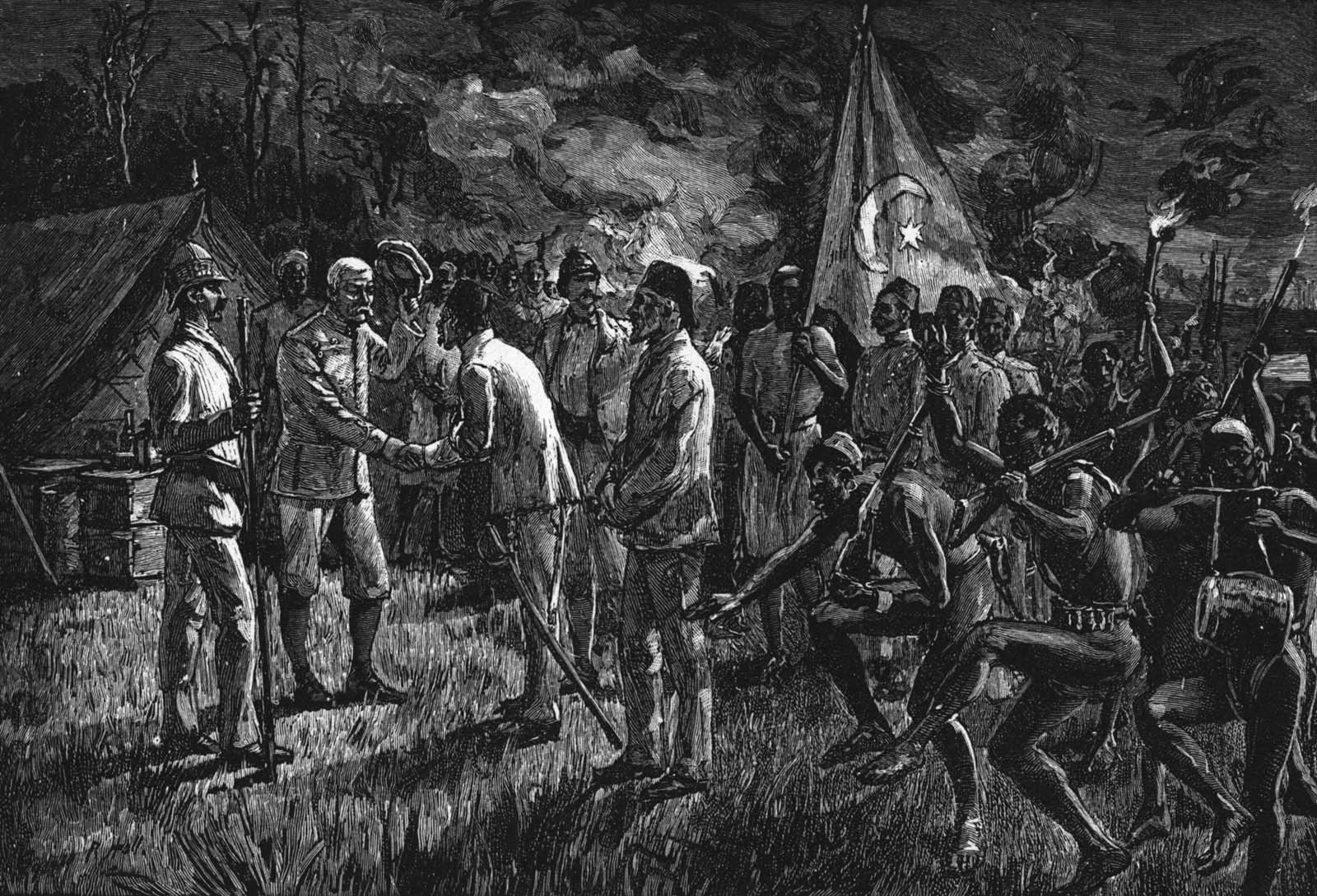

Emin and Casati Arrive. H.M. Stanley, Darkest Africa (1890).

A Lingering Darkness: A Love Affair with Colonial Culture

Fast forward to 1975, when a famous Nigerian author named Chinua Achebe penned a critique of Heart of Darkness. Achebe pointed out that while Conrad and the rest of his generation has passed on, “his heart of darkness plagues us still.” He argued that because of its permanent place in the canon of English literature, Heart of Darkness continued to reinforce Conrad’s ideas of Africa as primitive and dangerous, generation after generation. Achebe critiqued Conrad for using Africans as props for a morality tale about Europeans, rather than as people with their own stories. In Heart of Darkness, Africans have no names, and Conrad referred to them as childlike cannibals who speak unintelligible languages. Ultimately, Achebe felt troubled that people continued to accept the book as a literary masterpiece, while either ignoring or brushing aside the racially charged language within its pages.

Poster from Tarzan of the Apes. Credit: National Film Corporation, 1918.

We can trace many stereotypes associated with Africa to colonial culture from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As Achebe pointed out, such myths have outlasted colonialism itself. The majority of these narratives, just like Heart of Darkness, use Africa and its people as a mysterious, primitive, and dangerous backdrop to tell stories about European adventure and romance in the continent.

So why is it that the people you see during your Jungle Cruise are dark-skinned, “savage” spear throwers and a menacing (but charming) trader named Sam, who will trade two heads for one of yours? Over time, movies like Casablanca (1942) and the African Queen (1951), or books like Tarzan of the Apes (1940s) by Edgar Rice Burroughs, have helped to make these colonial narratives seem normal, natural, and admirable. Each year, companies release new movies, books, games, toys, and various attractions that perpetuate these colonial narratives as well. While we might not even realize it, these stereotypes are deeply ingrained in our cultural imaginations and continue to influence our collective understandings of Africa and the people who live there.

If you liked reading this Disney-inspired history article, be sure to SUBSCRIBE to get updates on new posts and other exciting Enchanted Archives news!

Ryan Minor

I grew up in Southern California about an hour away from Anaheim, and have been to Disneyland more times than I can remember! As a grownup, I study and teach African History. I currently live in Goleta, California with my wife, Brittney, who is a first-grade school teacher, and our two kids, Ben (age 9) and Chloe (age 8).

Sources

Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (1899)

Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart (1959)

Chinua Achebe, An Image of Africa (1975)

Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost (1998)