Project Future: A Tale of One or More Municipalities

By Rachel Basan Porter

It was the best of times and the worst of times for Walt and Roy Disney between 1963 and 1971. Just a few years after the brothers opened Disneyland in July 1955, their Florida Project took on fairytale proportions. This is the story of how two most unusual cities came to be in central Florida. It all began with an idea from one of America’s greatest imaginations: Walt Disney.

Wometco's Park Theatres sign announcing the upcoming Disney World attraction in Orlando, 1967. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

Disneyland was a great accomplishment for the Disney Company. But almost immediately after it opened, Walt realized that his first park was too small, and other businesses sought to capitalize on Disneyland’s success by building adjacent amenities that did not meet Disney standards. Walt wanted complete control that extended beyond the gates, so he began considering a new project. In 1963, after years of research, Disney determined that central Florida was the best location for his new and improved endeavor.

Walt knew that land prices would skyrocket when landowners heard “Disney,” so over a period of two years, Disney leadership employed covert tactics to purchase 27,400 acres of swamp and pastureland spanning two Florida counties – Orange and Osceola. Former US Intelligence Service agent Paul Helliwell worked with undercover Disney employees Robert Price Foster (a.k.a. Bob Foster) and the strategist Buzz Price (a.k.a. Bob Price) to keep Disney’s investment a secret. New companies with names like “Reedy Creek Ranch Lands,” and “Bay Lake Properties” were established so that the true investors would remain hidden. By June 1965, the desired land was secured; it had cost less than $200 per acre.

Fun Fact!

When Roy Disney accompanied “Bob Foster” on trips to Florida, he adopted the pseudonym “Roy Davis” to throw off any suspicion about who was purchasing so much land. Roy’s little brother, “William Brown,” also traveled to central Florida; however, he was more recognizable and was once asked for an autograph. Walt signed it William Brown. Disney’s company pseudonyms are memorialized on a Main Street windowpane at the Magic Kingdom. Can you spot them for yourself?

During the week of June 14, 1965, Disney officials met in Burbank, California, to strategize the unique Florida project operation, which they nicknamed Project Future. They had yet to disclose their real estate acquisitions to any Florida officials but knew that was the inevitable next step. Taxation and supporting infrastructure for the project were important issues. Company officials determined that Walt and Roy Disney must first quietly disclose their intentions to Florida Governor Haydon Burns. The plan was to secure his support and let his office make the official announcement. Once the project became public, Disney could seek legislation (state) and/or ordinances (county), depending on the advice of the governor.

Governor Burns was in a unique position. A recent change in Florida’s Constitution required him to seek reelection after just two years in office. Burns felt confident that escorting Disney’s economic engine into the state would secure his reelection (it did not, although Burns later reflected it was perhaps one of the most defining moments in his governorship). Along with the lure of a half-billion-dollar investment to the Florida economy, Paul Helliwell submitted Walt Disney’s wish list to the governor detailing the cooperation needed to build and operate the Florida attraction. This is where Disney first suggested to a Florida official that they could accomplish their goal by creating “one or more municipalities.” Walt Disney wanted his own autonomous city.

From left to right, Walt Disney, Governor Haydon Burns, and Roy Disney at the press conference announcing Disney’s investment in Orlando, Florida, November 15, 1965. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

Several months after Governor Burns privately committed to Disney, the official public announcement followed. On November 15, 1965, three hundred media, government, and business leaders joined the governor, Walt and Roy Disney, and their Project Future team at Orlando’s Cherry Plaza Hotel. The deal was sealed. Disney was assured that they had Florida’s support. Next, they had to convince the state legislature to allow Disney control beyond the theme park gates.

In October 1966, Walt starred in a film made for legislators that described his vision of the development. He wanted a theme park on the north east quadrant of his property, but he also wanted to build industry centers showcasing futuristic technologies. Most significantly, Disney wanted to build a unique city for his employees on the property. He described a progressive city plan he called the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (E.P.C.O.T.). Walt’s dream development in Florida was a city first and foremost, and theme park experience second.

Just over a month after filming and before the legislature had the opportunity to contemplate Walt’s ideas, he died. By that point, Roy and other Disney leaders were deeply committed to and invested in seeing the Florida project through.

Roy Disney and group watching as Governor Claude Kirk signs the Disney bill at the Governor's mansion - Tallahassee, Florida. May 12, 1967. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

With only the first iteration of Walt’s ideas in hand, the Disney team prepared three bills for the 1967 Florida Legislature and newly elected Governor Claude Kirk. The bills created an improvement district, within which two municipalities would operate. This arrangement allowed Disney to construct the specialized development (including a futuristic city), pay minimal taxes, and establish their own rules about how the land would be managed over the years.

The three Disney bills totaled 500 pages. Legislators were beseeched to “vote in favor of Mickey Mouse.” A vote against was seen as voting against families or motherhood. All three bills passed with only procedural amendments. Establishing the two cities – Bay Lake and Reedy Creek (later renamed Lake Buena Vista) - gave the Disney Company more autonomy than any Florida county. Disney suddenly acquired an airport, police and taxation powers, control over energy production (including approval to develop nuclear energy sources), and complete oversight of land development. Decades later a few legislators lamented how much control their laws gave to Disney, suggesting the Florida Government made the Walt Disney Company a sovereign entity.

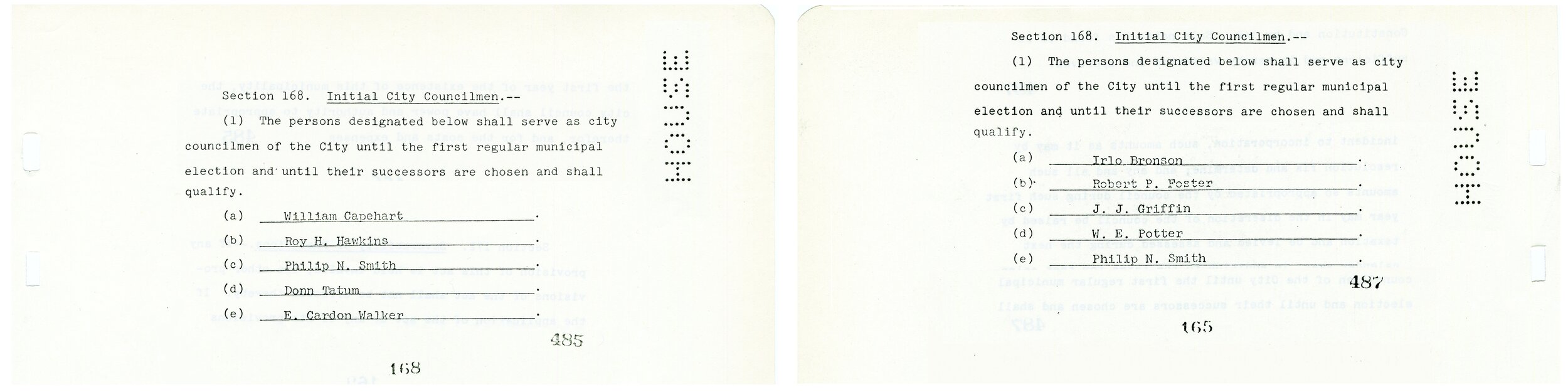

Disney went into the business of local government in 1967. Nine prominent Disney officials served as commissioners, including future Disney Production Presidents Donn Tatum and Card Walker. Former Central Florida Senator Irlo Bronson, whose family sold Disney some of the land, joined Robert – Bob - Foster in this new enterprise as well. Chapters 67-1104 (left) and 67-1965 (right), Laws of Florida. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

On October 1, 1971, the Walt Disney World Resort opened the Magic Kingdom. Roy Disney prioritized opening this part of the theme park without the futuristic city his brother had envisioned. The reimagined E.P.C.O.T. was planned to open on the heels of Magic Kingdom, but Roy Disney died later that year, and E.P.C.O.T. became a theme park instead of a futuristic housing solution. Nonetheless, Disney did realize the dream of developing a unique city. In fact, with the help of two governors and the 1967 Florida Legislature, they actually managed to create two.

View up Main Street in the Magic Kingdom - Orlando, Florida. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

Rachel Basan Porter is an historian and archaeologist who currently serves as the Director of Research and Programming at the Florida Historic Capitol Museum in Tallahassee, Florida.

About the Author

I have always loved telling stories, which is probably how I ended up working as an historian. In my professional life, I work in a museum and am responsible for sharing narratives through exhibitions and programs, as well as collections care and research. Whether it’s an evidence-based story that recreates a scene from a Paleoindian Era mastodon kill site (I am an archaeologist by professional training), or a children’s adventure through my adopted state of Florida, stories are at the heart of my career adventure. I have been lucky to have opportunities to write professionally and was showcased at the 2018 National Book Festival in Washington, D.C. I have lived and worked all over the world and draw inspiration from those experiences as well as my Cherokee Nation heritage. My two daughters who request “stories from my mouth” instead of from books remain my greatest inspiration to date.

Sources

Burns, Haydon. 1965-1966. "Governor's Correspondence, Series 131." State Archives of Florida.

Disney Studio Productions. 1966. Epcot/Florida Film. October 27. Accessed October 14, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sLCHg9mUBag.

Economic Research Associates. 1964. Preliminary Investigation of Available Acreage for Project Winter. University of Central Florida, Harrison "Buzz" Price Papers. 158, https://stars.library.ucf.edu/buzzprice/158.

Emerson, C. D. 2010. Project Future: The Inside Story Behind the Creation of Disney World. Ayefour Publishing.

Florida House of Representatives. 1967. "Proceedings at Tallahassee of the Forty-First Legislature." Journal of the Florida House of Representatives. Tallahassee. 127-130; 235-240; and 343-347.

Gong, Senator Edmond, interview by Florida Historic Capitol Museum. 2003. Oral History (November 14).

Horne, Senate President Mallory, interview by Florida Historic Capitol Museum. 2001. Oral History (April 16).

State of Florida. 1967. "Chapter 67-764, Laws of Florida." In Special Acts Adopted by The Florida Legislature at its Forty-First Regular Session, Volume I, Part Two, 256-358. Tallahassee: Florida Department of State.

State of Florida. 1967. "Chapter 67-1104, Laws of Florida." In Special Acts Adopted by The Legislature of Florida at its Forty-First Regular Session, Volume II, Part One, 200-301. Tallahassee: Florida Department of State.

State of Florida. 1967. "Chapter 67-1965, Laws of Florida." In Special Acts Adopted by The Florida Legislature at its Forty-First Regular Session, Volume II, Part Three, 3769-3869. Tallahassee: Florida Department of State.

State of Florida Library and Archives. Florida Memory. Accessed 2020. http://www.floridamemory.com.