A Short History of Tattoos

By Sasha Coles

Vases and artwork from the fifth century depict Thracian women with abstract designs or simple figures on their bodies.

On October 31, 1948, a Los Angeles Times article by Rhoda Roder told readers, “Not all tattooed people are in the circus.” While most Americans assumed that exclusively sideshow performers and sailors patronized tattoo artists, Roder explained how “these men with the needles actually get under the skin of people from almost all walks of life.” You could find hearts, flowers, Mickey Mouse figures, and elaborate re-creations of famous artworks on everyone from working-class folks and factory owners to fancy New York socialites. How do we make sense of Roder’s news-worthy announcement that in the 1940s, people from all different backgrounds liked tattoos? Let's go back in time to explore the historical roots of the practice and the diverse meanings attached to tattoos.

“The head of a chief of New Zealand” by Sydney Parkinson, the artist on Captain Cook's voyage to New Zealand in 1769. Click HERE for the source.

Tattooing has been a worldwide phenomenon for centuries. Scientists have located sixty-one tattoos on the body of Ötzi the Iceman, whose 5,300-year-old remains were discovered in September 1991. Archaeologists found tattoos on Egyptian mummies dating to 2100 BCE. Ancient Greek texts describe how the highlanders of Scotland and the Thracians, who lived in the area that is now Turkey, adorned themselves with markings to show membership in a clan or religious group. The Ancient Greeks, Persians, and Romans adopted tattooing as way to indicate someone’s status as a slave or criminal. Traditions of body-marking flourished among many other groups, including European peasants, alchemists, early Christians, warriors, and virtually all Amerindian nations.

The word “tattoo” came into usage in the 1700s, after Captain James Cook went to the South Seas. In Tahiti, Cook witnessed how “Both sexes paint their Bodys, Tattow, as it is called in their Language. This is done by inlaying the Colour of Black under their skins.” European explorers viewed this practice as proof of superstition, immorality, and barbarism. The Polynesian people, on the other hand, used tattoos as markers of strength, status, maturity, genealogy, health, balance, and spiritual connections. Sailors got tattoos as “souvenirs” of their visits to far-off lands in the South Seas and Asia. After learning the technique, they developed a distinct tattoo culture that helped them forge a sense of community.

In the nineteenth-century United States, tattoos became more popular and began to attract attention. Some scientists, reformers, and commentators viewed tattoos as an indication of criminal behavior and moral problems. Not everyone accepted the negative stigma attached to tattoos, though. They became more socially acceptable during and after the American Civil War, when soldiers used them to express loyalty to the nation. Martin Hildebrandt, the first “professional” tattoo artist, set up shop in the 1840s. Samuel F. O’Reilly revolutionized the industry in the 1890s, when he patented a handheld electric tattoo machine. The traditional method of tattooing involved rubbing pigment into a series of pricks made with a pointed stick or needle. O’Reilly’s device could make 3,000 pinpricks per minute. This machine quickened the process, decreased the pain for the client, and allowed for greater detail in color and shading. Hildebrandt, O’Reilly, and other early tattoo artists trained the next generation through an informal apprenticeship system, where less advanced artists would help around the shop and hone their skills and expertise.

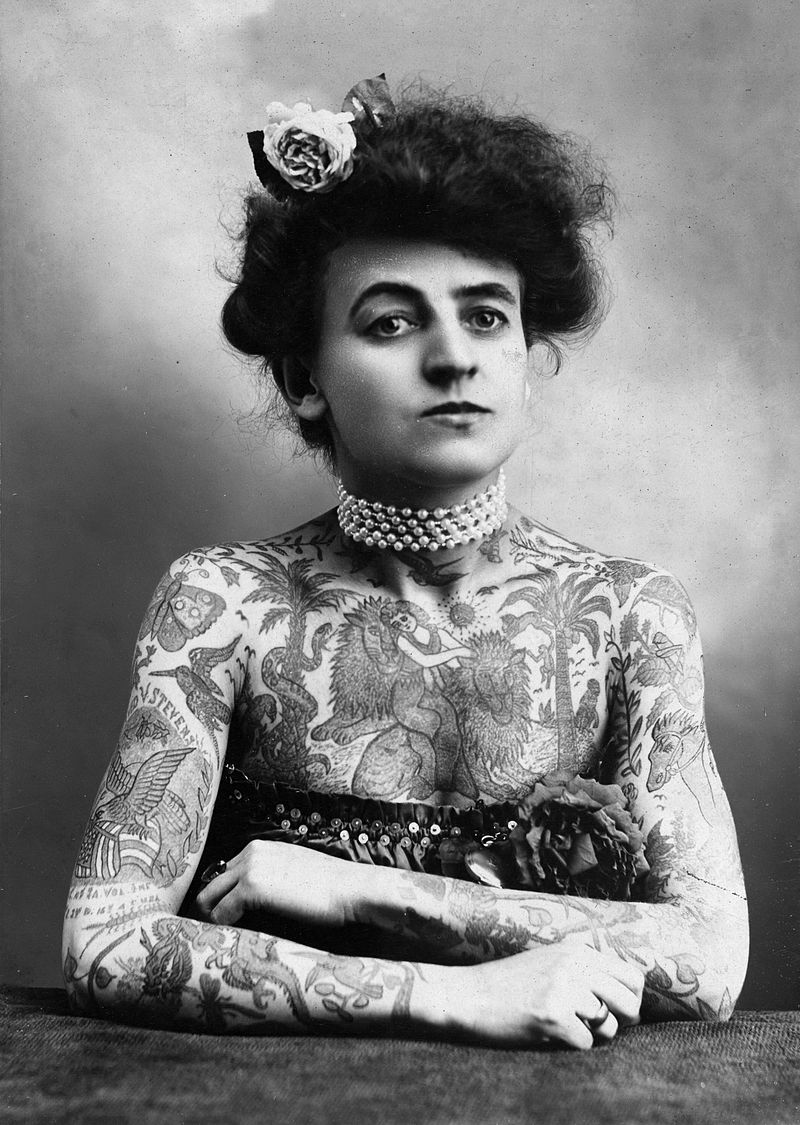

Some tattoo artists also made a living as performers. During the late 1800s and first half of the 1900s, tattooed men and women made pretty good money traveling around the United States as part of circuses and carnivals. Americans viewed them as thrilling and odd “attractions.” In those days, it wasn’t common to see a person covered in tattoos. Gus Wagner, one of the most famous “tattooed men,” got his start in the 1890s, when he voyaged around the world as a merchant seaman. After learning how to tattoo from people he met in Borneo and Java, he returned to Ohio with more than 260 tattoos. He started making a living as a tattoo artist and circus performer, billed as “the most artistically marked up man in America.” He also began tattooing his wife, Maude Stevens Wagner, a professional aerialist and contortionist. Maude learned how to tattoo and worked alongside Gus for many years. They even passed on the trade to their daughter, Lotteva. Tattooed men and women performers formed rivalries with one another, but they also established a supportive communication network where they shared information about circus companies and best practices for tattooing.

Maud Stevens Wagner with arms and chest covered in tattoos. Click HERE for the source.

Over the course of the twentieth century, the reputation of tattoos fluctuated. Military authorities discouraged soldiers in World War I from getting tattoos, because of their “inappropriate” content and perceived health risks. The practice also took a hit during the Great Depression, which severely limited the disposable income of many Americans. In this same period, teenagers began getting tattoos. As you might imagine, this made adults and local governments anxious. Lawmakers across the country called for more regulation based on “evidence” that tattoos caused shingles, leprosy, syphilis, and cancer. World War II partially rehabilitated the status of tattoos because of their prominence among soldiers, but the family-centered, suburbanized culture of the 1950s was not particularly friendly to tattoos. Many people viewed them as the purview of drunks, motorcycle clubs, street gangs, and other “deviants.” Cities in Oklahoma, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Arkansas, Tennessee, Ohio, Michigan, and Virginia even made tattooing illegal! A robust tattoo culture persisted, despite these negative stigmas and legal restrictions. A new generation of artist started to organize professional groups and push for more uniform ethical and hygiene standards to boost the legitimacy of their craft. By the 1970s and 80s, more people started to acknowledge tattooing as an art form. Now, tattoo shops and conventions dedicated to the craft proliferate.

My guess is that you either have a tattoo or know someone who does. A survey conducted by Statista in June 2017 found that four out of ten US adults aged 18 to 69 have at least one. As I was putting together this story about tattoos for the Enchanted Archives, I kept seeing beautiful pieces featuring Disney characters, scenes, and quotes on social media and in blog posts. I realized that I needed to find out more about people’s Disney-inspired tattoos. I knew that I didn’t just want pictures, though. I wanted to know what people’s tattoos mean and why they decided to get them. If the history of tattoos teaches us anything, it’s that these works of art are more than skin deep.

Want to know more about the history of tattoos? Click here for Episode 25 of the Main Street Style podcast. Maggie, Paola, Cailey, and I chat about Disney tattoos and the tattooed ladies of the nineteenth century, !

If you liked reading this Disney-inspired history article, be sure to SUBSCRIBE to get updates on new posts and other exciting Enchanted Archives news!

Teresa and Peter

@grimgrinningteresa and @grimgrinningpeter

To Infinity and Beyond!

Teresa and Peter got these Toy Story-inspired rockets done right after they got married. "We always tell each other that we love each other 'to infinity and beyond' (it was even in our wedding vows). We also love the whole Tomorrowland style of the retro future. My rocket ship is inspired by Buzz Lightyear’s colors and Peter’s is inspired by Woody’s colors." -Teresa

Merida

"I am very proud of my Scottish heritage, and when Brave came out, I felt really connected to it. I wanted something that really paid tribute to the movie but also had a bit or a twist to it. I wanted Merida to really look like a warrior." -Peter

Cinderella's Castle

"The first Disney Castle I ever saw in person was Cinderella's Castle. I remember so vividly entering Magic Kingdom and seeing it for the first time. I always wanted that feeling to stay with me, and every time I look at my forearm, I remember that moment." -Teresa

Alicia

@missaliciam

The Hitchhiking Ghosts

"The hitchhiking ghosts are basically in honor of my favorite ride. I have a love of horror and Disney, and the Haunted Mansion combines both haunt and Disney magic, so I love it! My dream is to visit all of the mansions internationally, and also to see the buildings they were modeled after." Alicia

Jiminy Cricket

"The Jiminy Cricket is because he reminds me of my dad and always letting my conscience be my guide! Be good, do good, and good comes back to you." -Alicia

Matt

@bigthunderdesigns

Pirates Jail Scene

"My tattoo is based on Marc Davis' concept art for 'Pirates of the Caribbean,' which was re-created almost exactly in the ride. This scene is one of my favorite examples of visual storytelling in the Disney parks, and it gets at what Imagineers do so well. It's full of detail and charm, and it helps build this rich world that captures the imagination. Even after 51 years, it still delights boatloads of guests. I work on museum exhibits, so this doesn't just represent my love of the parks. It's also a source of inspiration. Every day, I see it and think 'I'll make my jail scene someday.'" -Matt

Arica

@disneylandgrammers

Minnie Mouse

"My local tattoo shop was fundraising for animals in need, after being lost or abandoned due to a hurricane. My heart immediately knew I wanted a Disney tattoo. Disney has always been a part of my life as far back as I can think, to my earliest childhood memories. One of my favorite pictures when I was young was of me and my brother with Minnie Mouse at Disneyland. So this was me paying homage to something that will always have a place in my heart." -Arica

Ashley

@disneyawaits

Baby Rocket and Groot

"These two symbolize my brother and me. He's Rocket, and I'm Groot." -Ashley

Felix

@felixinfantasyland

Hakuna Matata

"Before my husband and I started dating, we got matching tattoos as friends--8 years ago. They mean a lot to me. We were both going through a hard time." -Felix

Chad

@hundredacrehoodco

Mickey Mouse

"Classic Mickey was my first Disney tattoo. I felt like that lil' mouse, with his hands on his hips and a big friendly smile, which just encompasses the magic and whimsy behind Disney. Honestly, I got it on my ribs, because I wear so much Mickey stuff that I didn't want it to be overkill. I can't NOT smile every time I see this lil' guy on my body-it makes me feel like the magic is a part of me." -Chad

Splash Mountain Vulture

"The vulture was done by my amazing friend and brand rep, @felixinfantasyland. This one has a couple of meanings for me. One, it's an homage to the Disney parks and all of the memories I have made there (WDW is my favorite place to be). Two, it also represents the darker side of Disney. I think our brand, Hundred Acre Hood, represents something a little different than the others, so this lil' bird on my shoulder is a reminder of that." -Chad

Sources

Arnaud Balvay, “Tattooing and Its Role in French-Native American Relations in the Eighteenth Century,” French Colonial History 9 (2008): 1-14.

Jane Caplan, editor, Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History (2000)

Jonathan DeHart, “Sacred Ink: Tattoos of Polynesia,” The Diplomat, November 25, 2016.

Carl Engelking, “Scientists Have Mapped All of Ötzi the Iceman’s 61 Tattoos,” Discover, January 30, 2015.

Michelle Myles, “Martin Hildebrandt’s Tattoo Legacy,” NeedlesandSins.com, January 16, 2015.

Amelia Klern Osterud, The Tattooed Lady: A History (2009)

![IMG_20180504_075531_376[1709].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59a0aee946c3c471fc619273/1525446136889-AZ87TM205GF7TJ2B8TEG/IMG_20180504_075531_376%5B1709%5D.jpg)